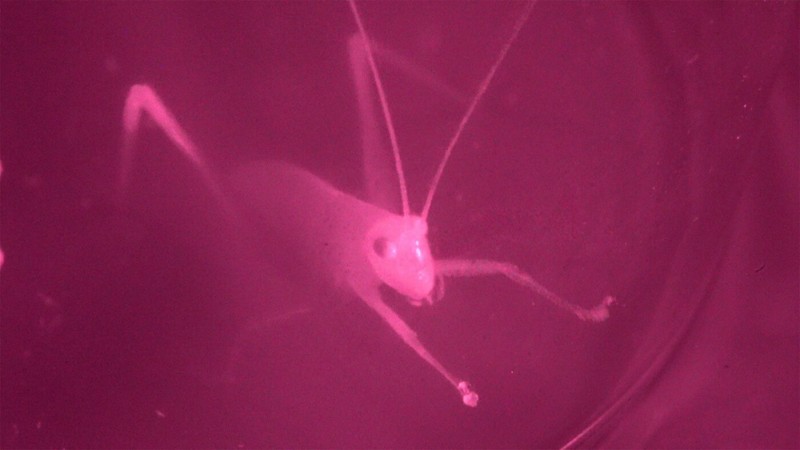

Exploring the corporeal vocabularies of silent crickets—and our anthropocentric impulse to index them—Madeline Hollander’s recent video work Flatwing (2019) documents her quest to capture their satellite strategies for survival. In tandem with Hollander’s solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, we spoke about cricket automatons, the persistence of vestigial choreographies, kinetic integrity, and the scientific method. Hollander’s quest to record the autopilot behavior of flatwings brought her to the island of Kauai where, armed with an infrared camera, she spent several nocturnal nights actively searching for them. Documenting the mute crickets’ bait-and-switch strategy may have proved “futile,” but Flatwing stages the dynamic of poiesis capture: crickets hobbling their courtship songs in exchange for life, and our unavailing demand to bear witness in exchange for choreographic fodder.

—Elizaveta Shneyderman

Elizaveta Shneyderman: Can you tell me about the origins of Flatwing?

Madeline Hollander: I first came across the story about the emergence of silent crickets while Googling where to buy live chirping ones in bulk. At the time, I was developing New Max (2018), a performance that used temperature as its choreographic axis point, and I had this fantasy of releasing hundreds of crickets into the gallery to create a live “temperature” orchestra. Crickets are essentially thermometers; their chirping rate correlates to the outside temperature, so they seemed like a fitting soundscape.

Scrolling through search results, I saw the headline, “The Silence of the Crickets,” and was immediately sidetracked. The article described a phenomenon in which due to rapid evolution the island Kauai was being populated by crickets with “flat wings.” This quick adaptation occurred because of an acoustically oriented parasitic fly that has been fatally attacking the chirping cricket population for decades. The only survivors of this air raid are those crickets with a rare genetic mutation: lacking the ridges on their wings required to make their mating call makes them essentially invisible to the enemy. The article detailed how, despite this mutation, the crickets continue to stridulate, going through the motions of rubbing their wings together to create the chirping sound. This last part was key because I needed to know what this silent mating song looked like and whether their motions were any different than those of the crickets who still had ridges on their wings and could actually chirp.

I reached out to Marlene Zuk, an evolutionary biologist who is one of the leading researchers on the topic, and quickly learned that there wasn’t any existing documentation of this mute, yet active, new species. Shocked, I rented an infrared camera and booked a trip to Kauai to attempt to capture these movements myself. The surreal, nearly impossible expedition proved futile; however, the footage and field recordings from this quixotic mission later became the material for Flatwing.

ES: What I find so potent about Flatwing is how it touches on the tension between romance (i.e., storytelling; extending faith to all possibilities; the opposite of the scientific method) and science (i.e., actual data capture; the indexical; proofs above all; crickets-as-automatons). This is all the more evidenced by the tension between your faith in the evolutionary futures for these crickets and their doubtless extinction. Can you speak to that?

MH: This tug-of-war between storytelling and myth—between field research and the scientific method—has been a recurring tension in my work, but Flatwing was the first piece that staged this dynamic front and center. In our conversations, Marlene repeatedly reminded me of my tendency toward anthropomorphism, reinforcing the idea that crickets are essentially automatons, hardwired to perform a set of movements whether or not they still produce sound. She would interject into my hypotheses by saying, “that is what YOU would do” and reminding me that “they [crickets] are not like humans.” But my choreographer brain was convinced that crickets could be innovative in their new situation and that they had the ability to learn and adapt to new environmental pressures, like learning to rub their wings against a blade of grass to mimic the sound of the chirp or to develop a mating dance to replace their muted courtship song. Marlene firmly shut down every one of my “romantic” theories, emphasizing the impossibility of these types of behavioral or phenotypic changes appearing within any individual cricket’s lifetime and how this type of adaptation would require many generations of evolution.

These crickets were running out of time. With their chirping counterparts quickly approaching extinction, there wouldn’t be enough future generations to even entertain the possibility of the emergence of a “survival dance.” Still, I’m not convinced that they won’t survive. The failure of my quest to uncover their moves doesn’t reflect the fate of their species.

ES: In some ways, Flatwing is indexing the incompatibility of the two methods. Is there more to understand about this friction between the forms of visualization captured data enables and the actual record or data?

MH: This friction is incredibly illuminating. It reveals all of the moments when our motivations either collide or miss each other altogether. Yet, our subjects and passion totally align. Marlene’s lab values numbers and specimens, and I value movement patterns. Our tools and approaches for obtaining these two forms of information are going to be fundamentally different: premeditated counting and measuring versus spontaneous observing and recording. But I don’t see any reason why these methods can’t be symbiotic. Before leaving for Kauai, I offered to send Marlene’s research lab the footage I was aiming to capture of silent crickets (if successful), but they were not interested.

Even if I had succeeded in documenting their silent jig or new mating behaviors, those movements would serve as inspiration for developing new choreographies, manifesting through a human form, not a cricket’s insect body. Any resemblance to the original movement would instantly become distorted (humans don’t have wings!). This is one of my favorite aspects of culling choreography from movement sources that can’t map directly onto the human body.

ES: I understand Flatwing is quite the departure from your choreographic work.

MH: I don’t see Flatwing as a departure but rather as a glimpse into my choreographic research process. Discovering articles about Kauai’s rapidly disappearing nightscape and the muting of a sound that, for me, functioned as a type of sonic horizon line resonated with themes encircling my recent work. The irony that these natural thermometers, the chirping crickets, are being replaced by silent ones, the flatwings, at a time when global average temperatures are rising due to the current climate crises, felt both ominous and precise. The loss of their song functioned like an alarm or an uncanny silence signaling the increasing frequency and magnitude of ecological and planetary disasters due to the climate crises. Also, the fact that this new population continues to rigorously perform their mating movements, expending huge amounts of energy to rhythmically open and close their wings to no avail, was exciting to me as a choreographer.

ES: I’m interested in this impossible death drive of yours to find and capture something you sort of knew was impossible (flatwing stridulation). It’s kind of like a choreographic/psychoanalytic extension back onto you in that you were so devoted to their satellite behavior that you also behaved in excess of your own faculties to index them. Where else did the research for Flatwing take you?

MH: My reaction was definitely excessive. I spent five nights hunting for silent crickets and only found katydids, cockroaches, beetles, wild boar, centipedes, cicadas, frogs, and chickens—no flatwings. It was very dark; it rained every thirty minutes; I couldn’t see anything without looking through the viewfinder of the infrared camera; and I was taunted by the cacophony of every other species’ mating calls. This desperate quest humorously aligned me and my stubbornness with these flatwings and their invisible mating dance. But I had convinced myself, despite expert advice, that the crickets were already developing their silent mating dance, only no one had witnessed it yet. I needed to know whether this was their last dance or their first.

My research on mating dances also led me to death dances, and in particular the Tarantella (1964), a maniacal ballet by the choreographer George Balanchine inspired by an ancient Italian folk dance rooted in paradoxical lore. The dance exists simultaneously as a frenetic jig that must be danced by someone bit by a venomous spider in order to sweat out the poison to prevent their own death and as a hysterical twirling trance induced by the venomous bite that only expedites the spread of poison through the veins and kills the afflicted. This fate is left to the viewer to decide. The Tarantella is the exact opposite of a mating dance, but its lethal conundrum stuck with me throughout making Flatwing, becoming somewhat of a metaphor for my trip.

ES: In your phone call with Marlene, included in the video, you also discuss the subtleties between miming an activity—in this case, cricket stridulations—and actually performing it. Can you tell me more about this distinction?

MH: This connects back to excess movement. I’m fascinated by vestigial choreographies, autopilot behavior, the ways we, both as individuals and collectively, “go through the motions” of an activity. Similar to a vestigial organ, a vestigial gesture is a “useless” movement that exists as a remnant of an outmoded movement that once evolved out of necessity. In this case, the silent crickets’ stridulation has become a vestigial choreography, and I’m still curious to discover the differences, even if microscopic, between silent rather than audible stridulation moves.

Kinetic integrity is also something that I think about a lot when choreographing: imagine playing an air guitar versus playing the instrument, miming opening a door versus opening the door, or lip-syncing versus singing karaoke. Both performances are real, but their physical and aesthetic qualities are distinct.

ES: Lastly, what’s next for you?

MH: This past year I came across several new research papers that show, contrary to expectations, the flatwings are still populating the island and vigorously performing these futile movements with no sign of slowing. For the first time the scientists are questioning whether or not there is any potential for this excess movement to acquire a new meaning or function. As of now, it’s unknown whether or not the entire cricket population will go extinct once the last chirping crickets die off, which could happen at any moment. Meanwhile the flatwings will continue to enact this silent dance, increasing and decreasing their rhythms as the temperature rises and falls.

Madeline Hollander: Flatwing is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City until August 8.

Elizaveta Shneyderman is an independent curator, artist, and researcher working in the fields of contemporary art and media studies. She holds an M.A. in Curatorial Studies from the Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College. Her interdisciplinary research focuses on the history and philosophy of new media materialities and the techniques which emerge from them, including their influence on corporality in the era of digital images. Shneyderma’s essays on contemporary art and visual culture have been published in Artforum, BOMB, The Brooklyn Rail, and Rhizome, among others. She lives and works in New York.