Emily Clayton’s practice of joining autobiography with a critique of the ideological formation of a given milieu uniquely examines how images inform the nuances of a locality’s culture. Such is the case with her new exhibition, Hydra, which turns rural and blue-collar histories—among many other material psychologies—into an evocation. Exploring the psychic-geographies of her hometown archive, Clayton reinterprets the type of rural, white, southern identity that became the status quo in Savannah, Tennessee. Embedded in these works are the signs and symbols that produce myths around racial-hierarchy narratives and the pageantry involved in controlling civic and community life.

—Elizaveta Shneyderman

Elizaveta Shneyderman

For its source material, your new body of work uses archival photography from a local newspaper called The Courier in your hometown in rural West Tennessee. What have you learned from this archive in regard to social formations as well as the attitudes and aesthetics of class?

Emily Clayton

The origin of the research starts with my relationship to my hometown’s newspaper. The Courier was the first place I experienced a record of public life, including the types of images included in the show. I grew up going to buy this paper every Wednesday night with my family, like hot off the press. It only cost fifty cents, and it was a big to-do in town. There would be a line of cars in the parking lot. Like a lot of local lore, what was published every week in The Courier was talked about around town the following week. A mention in the paper could mean validation if you were crowned queen in a beauty pageant, or condemnation if your arrest was reported in a section aptly titled “On the Record,” the local police blotter. In these social formations, repetition and sameness create the grounds for class structures, racial hierarchy, and civic control. The display in Hydra aims to edify these images as symbols and archetypes in the same way that reading the local paper did for me. Spending time with the archive, certain themes kept emerging, such as people holding dead snakes, men with freshly killed deer, the “trophy” photograph, high school, car wrecks, buildings on fire, rural living conditions, and Christmas. I was interested in these categories because the images glorify death, dominance, pageantry, beauty, and destruction. The process of making this work has been about analyzing how these cultural practices assume symbolic value. It is interesting to see how these images exist in a space in New York City where cultural capital can often sidestep traditional class hierarchies.

ES

And is that because cultural capital is something one can acquire in spite of wealth if you’re just cunning enough?

EC

I wish it was that easy. I think it is more complicated than wit or cunning. The system is pretty opaque, and it seems as if the goalposts keep moving.

ES

Describe the installation of your work at Smack Mellon as it relates to its content.

EC

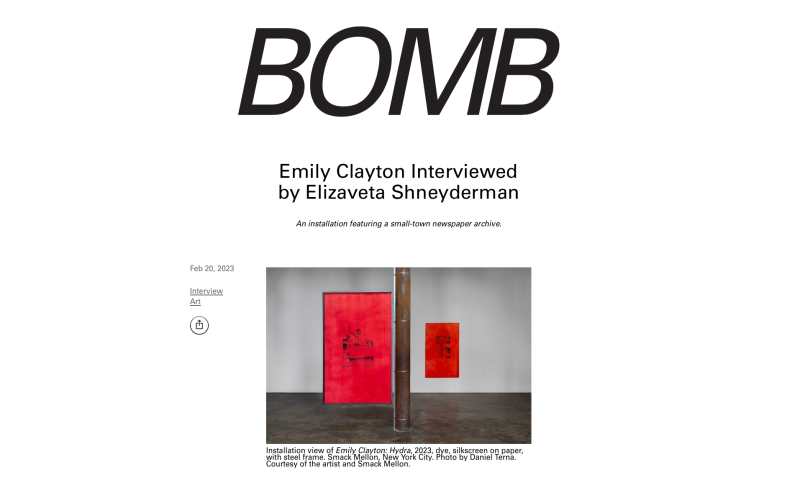

When I was invited to do an exhibition at Smack Mellon, I wanted to respond to the unique architecture and use it as an organizing principle for the works. The building is in a former industrial space that housed a boiler facility that fueled the neighborhood factories. The ceilings are high, and there are thirteen columns that bisect the gallery. I used the columns to determine the visual logic of the show. The works are large, double-sided, photographic silk screens and drawings on paper displayed on steel armatures that allow them to be viewed from both the front and the back. The steel armatures are strapped to the columns to form corridors and passageways between the pieces. There are also other works that break that logic. I was thinking about the idea of a processional and how to disrupt it. These are photos of people from a small town, so the installation is meant to emphasize that insularity and form connections that reflect the intersubjectivity between the images which are of white, rural, southern, lower-class Americans. I thought a lot about how the pacing of the works in the space connects syntactically between the images and how the scale corresponds to the architecture of the space. I welded the armatures myself, which was important to me due to their relationship to space and to my own body. My dad was an industrial pipefitter in nuclear plants throughout the Southeast. On a personal level, it was exciting to do this labor in memory of him.

ES

How did you arrive at this process of silk screening onto paper, and what was behind the decision to make them double-sided as well as to include these “expressionistic” drawings?

EC

I came to silk screen through another project, Someone Thinking of You (2020), where I was working with large pages of text pulled from an erotica manuscript I was commissioned to write. Since the book was never published, I reproduced pages of the manuscript using a large-format silk screen. Writing erotica shifted my practice and allowed me to consider my experience as malleable source material. For me, silk screen fits into that way of thinking in terms of its relationship to authorship and appropriation, like the way Cady Nolan used silk screen and Adrian Piper used the newspaper as a timestamp and an index to point to social conditions. When I decided to use a newspaper archive from the mid-1970s to the early ’80s as source material for this exhibition, continuing to work with silk screen made sense. I am interested in the newspaper’s relation to reproducibility both art historically and in relation to the time period of the archive.

With the drawings and mark-making—which coexist with the silk screens, recto/verso—I wanted to combine something expressive with the silk screen to get at the psychology of the images, like the town’s people holding up the dead snakes. With that in mind, I made the works double-sided to consider inversions: the contrast between public and private, personal and social, and cultured and uncultured. In a lot of ways, it’s a reaction to my complicity inside of the system where I was raised.

ES

Despite the objective display strategy of the work, the images you’ve chosen are mediated by your own taste. At the same time, they are subject to the relationships within the frame and to the broader exhibition dynamic.

EC

The exhibition ecology is based on the idea of doubling, proliferation, and the mechanics of a small town. With the title, Hydra, you have the snake that grows two heads when one is cut off; and in the exhibition, the front and the back of the works play with the two sides: an exterior and interior. Within the photos from the archive, there is the multiplication of objects and animals held up square and direct to the camera. Here I’m thinking about how ideologies form through repetition, consumption, and myth, using the columns in the space, the color red, and the images to play out these extremes. Through my edit of the archive, I see the images relating directly to issues of today.

Two red vertical banners with a black-and-white photograph printed on them and attached to a metal pole.

ES

Does the title Hydra relate to the snake trophy?

EC

It does. The title of the show makes reference to the Herculean-Hydra Greek myth. Hydra was a nine-headed serpent creature that was defeated by Hercules in one of his labors. The evocative thing about Hydra, especially aesthetically, is that every time one of its nine heads is cut off two more would grow back in its place. Through this multiplying, I’m thinking about the Hydra in relation to different ideas of group identity and multiplicity. The metaphor was also used frequently from English colonial expansion all the way to industrialization to condone violence and describe the difficulty of imposing order over global systems of labor in order to mold capitalism. To this extent, John Adams even proposed “The Judgment of Hercules” be the seal for the new United States. The photos from the archive in a sense could hold both positions: Hercules and Hydra. On the one hand, they are the ruling class asserting power over living things in a false search for divine power, but at the same time they could be part of the proletariat, maybe.

ES

It’s fascinating to see these images of rural American in conjunction with images coming out of the Cold War at the time, which was in its later stage. Some of these images even strike me as corollaries to the forms of ideology-building that are subtextually charged in nation-states and national identity.

EC

Totally. I feel like they have the same bleakness as Cold War imagery. I see mythmaking embedded in the pageantry in so many of the photos. The people seem familiar with the scenarios they are replicating, which is how ideology-building remains present. I think much of this is an embodiment of the Lost Cause Narrative, which is a historical myth that casts sympathy for the Confederate defeat in the Civil War and denies the oppression and the legacy of slavery. The signs, symbols, and violence behind this mythology are present in so much of the archive. Hydra is a lot about examining how these scenarios and scenes repeat in the images in order to perpetuate racial hierarchy and allow class divides to persist.