Ilya Fedotov-Fedorov’s explorations of ecology, otherness, biomorphism, and taxonomies are heavily influenced by his experiences of alienation while growing up in increasingly untenable environments, from ostracizing doctor offices to homophobic schoolyards in Russia. Engaging with contemporary critiques of anthropocentrism, Fedotov-Fedorov’s practice incorporates painting, choreography, sculpture, and mask-making to deconstruct notions of what is “natural.” In turn, Fedotov-Fedorov renews a focus on processes in the natural world.

—Elizaveta Shneyderman

Elizaveta Shneyderman

Tell me about the title of your current exhibition, Snake Changing Skinfragment.gallery/exhibitions/54-snake-changing-skin/overview. It elicits a sense of turnover or regrowth. Does this apply to the content of the exhibition?

Ilya Fedotov-Fedorov

The idea for Snake Changing Skin came from an instinct to consider loneliness and connect with my childhood, specifically the protective sheath of disassociation and otherness that I wore as a kid in order to escape the world. This instinct, and the ways I’ve grown from it, became the content for the work and exhibition.

As a kid, I was always an outsider—maybe because I was gay or because I had bad health. My solution was self-isolation. I disassociated from people and from my body and looked to other species for support and guidance. Watching cartoons and movies, I realized that I saw myself with “outsiders animals” such as snakes, frogs, spiders, bats, and so on. In terms of cultural representation, they were usually the characters on the fringes. Slowly it became easier to imagine myself as an animal rather than as a human. So I played with insects and plants, entertaining an intense bodily and personality dissociation.

This exhibition is about loneliness and otherness, about interspecies connections, disassociation from your own body, trying to become someone else, the idea of creature. I really like the term “creature” for its implications of being not quite animal, not human, but something else entirely without type, species, gender, something alive, undead—a zero point.

ES

How has moving to the US changed your experience of making work?

IFF

It was not easy to be fully functioning in Russia as a gay artist, but it was even more complicated to work with queer topics. I experienced intense bullying and harassment at school; I had my arms broken five times and suffered a concussion, which led to me being hospitalized. This experience had a major impact on me, and for a long time I self-censored my work.

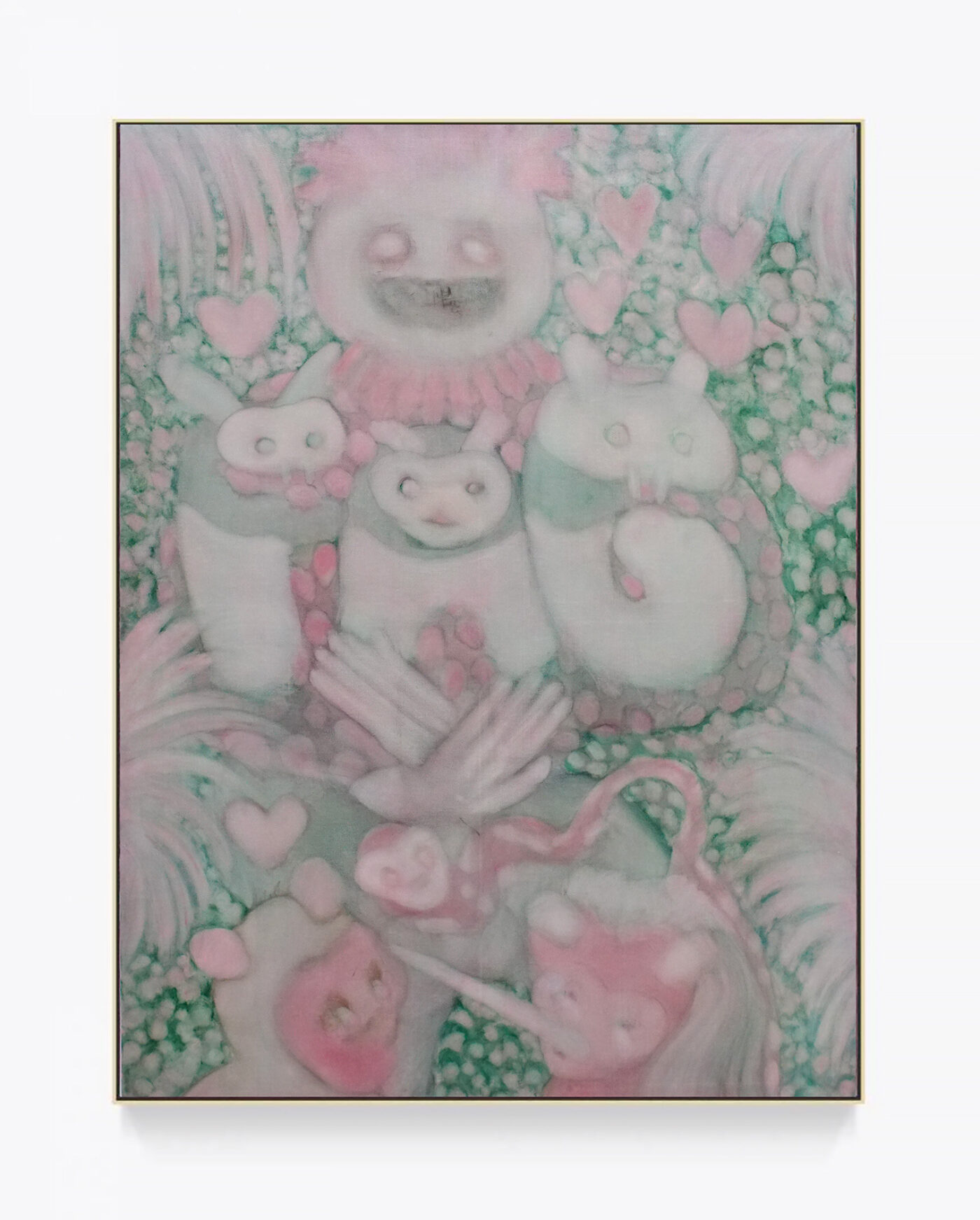

To be honest I thought New York City would be a perfect place for me to gain comfort and move on. I was delusional. But recent experiences of bullying and abuse in a New York gallery triggered me a lot and made me observe my own escapism. But it was time to change this pattern. I started to look at my work from a personal perspective and incorporate my experiences into the work. The family portraits series, for example, was an attempt to think with my experiences. The paintings depict unknown animals/humanoids as a group family portrait. In the portraits I am trying to convey the idea of my perfect family, a family composed of outsiders, of creatures—a group of friends I never had. One also could find these works as self-portraits with stories behind them.

ES

Why do you think it is that your version of escape is predicated on this sense of animal-human surrogacy?

IFF

That’s interesting. I’ve thought about why exactly I am interested in this biomorphic type of escape. Another personal story comes to mind. I was born with a rare kidney anomaly. I am a statistical anomaly. Growing up, I spent a lot of time in hospitals, often as the subject for research by doctors. They objectified my body. I was excluded from sports and was always the weakest, skinniest person in school, which made me a perfect target as weak, femme, silent, gay. Bingo! I don’t want to sound too dramatic because my body helped me a lot as it was easy to hide in small places and corners. Unfortunately, my physical appearance caused even more bullying and created more dissociation in my childhood. This interest in difference made me pursue a degree in biology with a particular focus on genetics.

Art helped me overcome my disassociation. In my Transiberia project, which was made in Venice at Istituto Santa Maria della Pieta toward the end of the 2019 Venice Biennial, I made a work about gender. In a big fish tank, I assembled ten African cichlids. At the start of the exhibition they were all female, but by the end they changed their sex and became all male. In preparation for this installation, I bought a mask of a woman with long hair, but didn’t in the end use it for the aquarium. Instead, I tried it on myself. I started recording and observing myself wearing this “woman” mask. One day I put myself “inside” the aquarium with the gender-changing fish, embedding myself in the process. This recording became my first video work, the bat and the snake girlfriends of the octopus (2019–20). It was my first close look at my body, though still with an element of disassociation, even if I knew it was me. The work was a complicated, rich, multilayered experience with references from my childhood about my health, weakness, femininity and masculinity, fragility, and awkwardness coming to the surface. From this experience, I decided to film myself, which later became the basis of my video and choreographic work. And you can see one of them in the show.

But it’s important to return to disassociation. Because of the mask, I was not really conceiving of the image I reflected back to me as my own body. Prior to this there were no humans in my work. It was a turning point because through these fish and the project I began to think about my identity and my relation to humanness and sexuality. This was also when I came out to my family. It was a very strange cycle: first I associated myself with strange creatures and animals, and then those creatures and animals helped me find myself as a human being.

ES

This reminds me of drag as a category of masking-to-unmask, so to speak; its quality of transition highlights differences.

IFF

I think I’m interested in the process of transition, but it’s not specifically about gender. For me, it’s any kind of transition. In my practice, when I work as a choreographer with dancers and even when I film myself, I focus more on the points of transition, paying attention to the very thin line between—between gender, between humanoid/creature. In this regard, the work is agender or without gender.

This is much more interesting for me. The characters in my work are “neutral,” like an egg or embryo, which becomes a starting point for a conversation on what neutral even is or how wide the spectrum is. This is also why certain animals figure into my work. Recently, I’ve used octopuses, butterflies, and bats as inspiration because of their unique gender qualities. I would say I am very curious about an impossible “it”—the creature character with a blurry identity. That’s why I’m trying different techniques and methods to find out.

ES

What media formats are present in the exhibition, and how has working across media shifted the presentation of your interiority?

IFF

Materially speaking, the exhibition has a variety of components, including sculptures, paintings, and video works. I’m also planning a performance throughout the run of the show. Most of my sculptures are related to the video works as extensions of the body. The sculptures act as a “glue” connecting the videos to the paintings. There are mostly masks and some body parts, as well as research from the perspective of dolls and horror movies.

I’m also realizing how different media inform my way of working. I realized that when I’m trying to speak about personal issues, it’s hard to present my thoughts in a very conceptual or rational form. This makes video work a challenge, because for video you need a screenplay, and when you’re working with other people you need to be very logical. There is not much time to stop and reflect. But making a painting provokes a very strange power of self-reflection. It’s almost impossible to get lost creating video, installation, or sculpture because you can fuck up. But it’s possible to get lost in painting. I have to confess I was underestimating painting before. I’m glad I’ve discovered its possibilities now.

A ghostly gray and white painting of a cluster of amorphous animals.

ES

Where will you get lost next?

IFF

I’m planning to continue my video, and I want to work with dancers, as I found several interesting dancers here in New York. I’m planning to make a full performance as a collaboration and a video. It’s my second year in New York, so I’m still in the process of organizing everything. I’m excited about what’s next.